- What exactly are deepfakes again? A refresher

- How are deepfakes created?

- The good – an optimistic view

- The dangers of deepfakes

- What can we do to tell fake from real?

- The future of fake and other considerations

Despite an increasing number of positive applications, the dangers of deepfakes continue to elicit widespread concern as they become more widely known and understood. We’re bombarded with content detailing the incredible speed at which this deep learning technology is being developed, how deepfakes are becoming increasingly sophisticated and more easily accessible, and what the risks are when this tech falls into the wrong hands. Whether we like it or not, and no matter how troubling the negative implications of the use of deepfakes may be, they’re not going anywhere. They’re here to stay. But aside from the negative press deepfakes have been getting, there seem to be many reasons to be excited about this technology and its many positive applications as well. For instance, deepfake tech will enable entirely new types of content and democratise access to creation tools that have, until now, been either too expensive or too complicated to use for the average person. On the whole, the ability to use artificial intelligence to create realistic simulations might even be a positive thing for humanity.

What exactly are deepfakes again? A refresher

It’s not easy to agree on a comprehensive definition of deepfakes, but let’s give it a try. The term deepfake combines the words deep (from deep learning) and fake. We know that deepfakes are enabled by deep learning technology, a machine learning technique that teaches computers to learn by example. Deepfake technology uses someone’s behaviour – like your voice, imagery or typical facial expressions, or body movements – to create entirely new content that is virtually indistinguishable from authentic content. This technology can also be used to make real people appear to say or do things that they never said or did, or to replace anyone in an existing video, or create video content with either completely non-existent characters, celebrities, or important political figures. The manipulation of existing, or the fabrication of new digital imagery is not new – in fact, AI-generated pornographic content first surfaced in late 2017. And while creating these types of effects used to take experts in high-tech studios at least a year to accomplish, the rapid development of deepfake technology in recent years has made the creation of really convincing fake content a lot easier and faster. Initially used to describe specific pornographic content, the term deepfakes is now being used more broadly and can refer to a host of different AI-generated, or synthetic, video content.

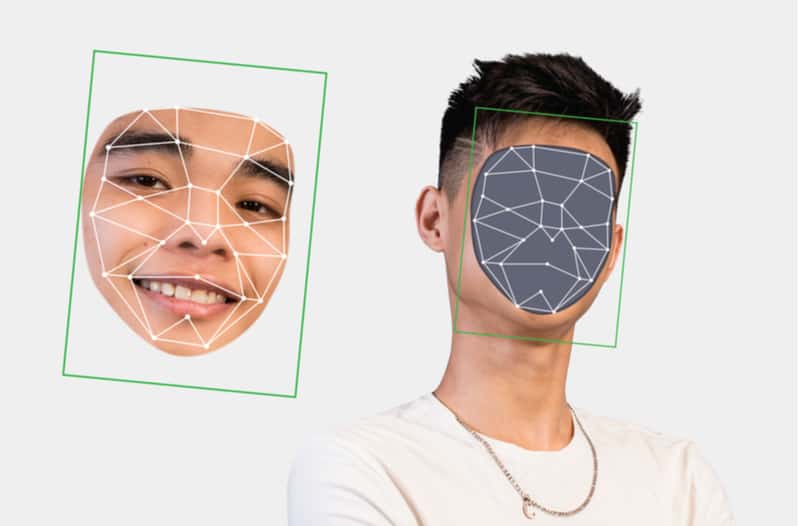

How are deepfakes created?

To create a realistic deepfake video of an existing person, a neural network traditionally needs to be trained with lots of video footage of this person – including a wide range of facial expressions, under all kinds of different lighting, and from every conceivable angle – so that the artificial intelligence gets an in-depth ‘understanding’ of the essence of the person in question. The trained network will then be combined with techniques like advanced computer graphics in order to superimpose a fabricated version of this person onto the one in the video. Although this process is a lot faster than it was only a couple of years ago, getting really credible results is still quite time consuming and complicated. The very latest technology, however, such as Samsung AI technology that has been created in a Russian AI lab, makes it possible to create deepfake videos using only a handful of images, or even just one.

Some notorious deepfakes that recently made the headlines:

A fake video of Mark Zuckerberg, created by two artists, in collaboration with advertising company Canny, showed up on Instagram. In the deepfake, Zuckerberg gives a rather sinister speech about the power of Facebook.

Another fake video shows former President Barack Obama calling President Donald Trump a “total and complete dipshit”. Halfway through the video, it becomes clear that Obama actually never said these words – they were actually from writer and ‘Get Out’ director Jordan Peele.

And by far one of the most realistic deepfakes around at the moment are these very recent ones that showed up on TikTok, in which you can see Tom Cruise (or is it?) sharing videos of himself playing golf and goofing around.

The good – an optimistic view

While the less-than-kosher uses of deepfakes are frightening to imagine, there are also many advantages to this technology, and new, good uses for deepfakes are found on a regular basis. Think, for instance, of editing video footage without the need for doing reshoots, or recreating artists that are no longer with us to perform their magic, live. Researchers at Samsung’s AI lab in Moscow, for instance, recently managed to transform Da Vinci’s Mona Lisa into video. They used deep learning to enable this famous lady to move her head, mouth, and eyes. Deepfake tech was also used at the Dalí Museum in Florida to display a life-sized deepfake of the surrealist artist delivering a variety of quotes that Salvador Dalí had written or spoken during his art career. Deepfake technology will enable us to experience things that have never existed, or to envision a myriad of future possibilities. Aside from many different potential applications in arts and entertainment, think of all the magic this tech could do in education and healthcare. Stay tuned for some more interesting examples of this groundbreaking technology.

Voice manipulator produces speech from text

Adobe’s VoCo software – which is still in its research and prototyping stages – enables you to produce speech from text and edit it just like you would images in Photoshop. So, let’s assume you would like to have your film clip narrated by, say, David Attenborough or Morgan Freeman; VoCo will make this possible without paying top dollar for actual top narrators doing the job. How the software works is that it takes an audio recording and alters it by including words and phrases that the original narrator never actually said. At a live demo in San Diego, an Adobe operator took a digitised recording of a man saying “I kissed my dogs and my wife” and changed it to “I kissed Jordan three times”. All it took to get to this result was to start off with a 20-minute voice recording, alter the transcribed version of the text and then press a button – creating the altered voice clip. As impressive as this may be, developments like this could further fuel the already problematic fake news issues and undermine the public’s trust in journalism. Adobe, however, has said it’s taking action to address these potential challenges.

Convincing dubbing through automated facial re-animation

Synthesia, an AI software company founded by a team of researchers and entrepreneurs from Stanford, University College London, Cambridge, and Technical University of Munich, is pioneering a new kind of media – facial re-animation software – for automated and very convincing dubbing. The AI startup was put on the map with the introduction of a synthetic video featuring David Beckham talking about raising awareness about the deadly disease Malaria in nine different languages. This technology can be used in various ways and can expand the reach of creators around the world. Synthesia and international multimedia news provider Reuters recently collaborated to create the world’s first synthesised, presenter-led news reports. To do this, they used basic deepfake technology to create new video reports from pre-recorded clips of a news presenter. By far the most remarkable is that this technology enables the automatic generation of video reports that are personalised for individual viewers. In learning and development, Synthesia’s technology can be used to create video modules in over 40 languages and to easily update and create new content. For corporate communications, the tech can help turn text into video presentations within minutes and easily turn slides into videos without the need for video editing skills.

Deepfakes can make anyone dance like a pro

Tinghui Zhou, co-founder and CEO of Humen AI, a startup that creates deepfakes for dancing, and his research colleagues at UC Berkeley, use a type of artificial intelligence called generative adversarial networks (GANs) to read someone’s dance moves and copy them on to a target body. With this technology, you can make anyone dance like, for instance, Bruno Mars. The system can be used for all kinds of dance styles – such as ballet, jazz, modern, or hip hop. First, videos of the source dancer and the target dancer are recorded. Then, the dancers are transformed into stick figures. After that, the swap happens, with a neural network synthesising video of the target dancer, based on the stick figure movements of the source dancer – and, voilà! All it takes is a bit of video footage and the right AI software. It’s impressive work, and this type of video manipulation would traditionally take an entire team a couple of days to do. Humen AI aims to turn the dance video gimmick into an app and, eventually, a paid service for ad agencies, video game developers, and even Hollywood studios. Ricky Wong, cofounder of Humen AI, says: “With three minutes of footage of movement and material from professionals, we can make anyone dance. We’re trying to bring delight and fun to people’s lives,” while Zhou adds: “The future we are imagining is one where everyone can create Hollywood-level content.”

Smart assistants and virtual humans

Smart assistants like Siri, Alexa, and Cortana have been around for a while, and have significantly improved in recent years. They do, however, still feel more like a new user interface that you need to give exact instructions to, instead of a virtual being you can interact with in a more natural way. And one of the most important steps toward creating credible virtual ‘human’ assistants that we can interact with is the ability to mimic faces, expressions, and voices. These so-called virtual humans are slowly but surely entering the mainstream in the form of digital influencers that we interact with the way we interact with other people. And while digital influencers don’t really respond to you in their own words as their content is created by storytellers, they are heralding a future of ‘natural’ interaction with true virtual beings. So, deepfake tech that is trained with tons of examples of human behaviour could give smart assistants the capacity to understand and produce conversation with lots of sophistication. And thanks to this same technology, even digital influencers could develop the ability to visually react – in real time – in credible ways. Welcome to the future of virtual humans.

Deep generative models offer new possibilities in healthcare

Deepfake technology can also have many benefits in other areas, such as healthcare. The tech can be used to synthesise realistic data to help researchers develop new ways of treating diseases without being dependent on actual patient data. Work in this area has already been carried out by a team of researchers from the Mayo Clinic, the MGH & BWH Centre for Clinical Data Science, and NVIDIA, who collaborated on using GANs (generative adversarial networks) to create synthetic brain MRI scans. The team trained their GAN on data from two datasets of brain MRIs – one containing approximately two hundred brain MRIs showing tumours, the other containing thousands of brain MRIs with Alzheimer’s disease. According to the researchers, algorithms trained with a combination of ‘fake’ medical images and 10 per cent real images became just as proficient at discovering tumours as algorithms trained only with real images. In their paper the researchers say: “Data diversity is critical to success when training deep learning models. Medical imaging data sets are often imbalanced as pathologic findings are generally rare, which introduces significant challenges when training deep learning models. We propose a method to generate synthetic abnormal MRI images with brain tumours by training a generative adversarial network. This offers an automatable, low-cost source of diverse data that can be used to supplement the training set.” As the images are synthetically generated, there are no privacy or patient data concerns. The generated data can easily be shared between medical institutions, creating an endless variety of combinations that can be used to improve and accelerate their work. The team hopes that the model will help scientists generate new data that can be used to detect abnormalities quicker and more accurately.

The dangers of deepfakes

As exciting and promising as deepfake technology is, there are very real threats as well. One of the most significant ones being non-consensual pornography, which accounts for a terrifying 96 per cent of deepfakes currently found online, according to a DeepTrace report. There have also been several reports of deepfake audio being used for identity fraud and extortion. The use of deepfakes has the potential to be a huge security and political destabilisation risk, as the technology can be used to spread fake news and lead to an increase in fake scandals, cybercrime, revenge porn, harassment, and abuse. There’s also a pretty good chance that video and audio footage will soon become inadmissible as evidence in court cases as deepfakes are becoming increasingly indistinguishable from authentic content. According to the Brookings Institution, the social and political dangers posed by deepfakes include “distorting democratic discourse; manipulating elections; eroding trust in institutions; weakening journalism; exacerbating social divisions; undermining public safety; and inflicting hard-to-repair damage on the reputation of prominent individuals, including elected officials and candidates for office.” Deepfakes can cause serious financial problems, too. Some examples include a UK energy firm that was duped into a fraudulent $243 million transfer, and an audio deepfake that was used to scam an American CEO out of $10 million. And we have some more examples for you, so read on.

New Year’s video address provokes attempted military coup

The fact that more and more – and increasingly sophisticated – deepfakes are circulating on the internet will progressively mean that any video that seems slightly ‘off’ can potentially cause chaos. One example is Gabon’s president Ali Bongo’s New Year’s video address in 2019. As the president had been absent from the public eye for some time, and the government’s lack of answers was only fuelling doubts, the video caused people in Gabon, as well as international observers, to grow increasingly suspicious about the president’s well-being. The aim of the video was to eliminate any speculations, but this plan backfired, as Bongo’s critics weren’t convinced of its authenticity. A week after the release of the video, Gabon’s military attempted an ultimately unsuccessful coup, citing the awkwardness of the video as proof that something wasn’t right with the president. Hany Farid, a computer science professor who specialises in digital forensics, says: “I just watched several other videos of President Bongo and they don’t resemble the speech patterns in this video, and even his appearance doesn’t look the same.” Farid added, while noting that he was unable to make a definitive assessment, that “something doesn’t look right.” The fear of deepfakes’ potential to sow this type of discord has caused the US and China to discuss new legislation and the Pentagon’s DARPA to invest in technology to detect fake content.

Deepfakes used to blackmail cheerleaders

Images taken from social media accounts have recently been used by a mother from Pennsylvania in the US to create incriminating deepfakes to get her daughter’s cheerleading rivals expelled, so that her daughter’s team, who competed against other high school teams, could win a competition. The woman had manipulated the images of her daughter’s opponents to show them in compromising positions, drinking, smoking, and even naked. The woman also sent the girls disturbing messages in which she urged them to kill themselves. The police have not taken action against the daughter, as there is no evidence that she was aware of what her mother was doing. The mother, however, is facing misdemeanour allegations of cyber abuse and related offenses. Bucks County DA Matt Weintraub says of the first victim: “The suspect is alleged to have taken a real picture and edited it through some photoshopping app to make it look like this teenaged girl had no clothes on to appear nude. When in reality that picture was a screengrab from the teenager’s social media in which she had a bathing suit on.”

Deepfake bots on Telegram create nudes of women and children

Last year, more than 100,000 deepfake images depicting fake nudes were generated by an ecosystem of bots, requested by Telegram users. The focal point of this ecosystem is an AI-powered bot that enables users to ‘strip’ the clothes off images of women, so that they appear naked. According to a report by visual threat intelligence company Sensity, “most of the original images appeared to have been taken from social media pages or directly from private communication, with the individuals likely unaware that they had been targeted. While the majority of these targets were private individuals, we additionally identified a significant number of social media influencers, gaming streamers, and high profile celebrities in the entertainment industry. A limited number of images also appeared to feature underage targets, suggesting that some users were primarily using the bot to generate and share pedophilic content.” The deepfakes have been shared across various social media platforms for the purpose of public shaming, revenge, or extortion. Most deepfake bots make use of DeepNude technology, but similar apps have started popping up across the internet. All you have to do is upload a photo, and a manipulated image is returned within minutes. Unfortunately, as Telegram makes use of encrypted messages, it’s easy for users to create anonymous accounts that are virtually impossible to trace. And while the objective of encryption technology is to protect privacy and assist people in evading surveillance, it’s easy to see how these features can be abused.

What can we do to tell fake from real?

As it stands, the number of deepfake videos circulating online has been increasing at an astounding estimated annual rate of 900 per cent. As technological advances have made it increasingly simple to produce deepfake content, questions are being raised about ways to prevent the malicious use of this technology. One way, just like in the case of cybercrime and phishing, is to raise public awareness and educate people about the dangers of deepfakes. Many companies have launched technologies that can be used to either spot fake content, prevent its spread, or authenticate real content using blockchain or watermarks. The downsides are, however, that these detectors or authenticators can also immediately be ‘gamed’ by those same malicious actors to create even more convincing deepfakes. We’ve gathered some examples of technologies that have been developed to combat the misuse of deepfakes.

Social media deepfake policies

Social media networks play the most important role in ensuring that deepfakes aren’t used for malicious purposes. Basically, their policies currently treat deepfakes like any other content that is misleading or could lead to people getting hurt. For instance, Instagram’s and Facebook’s policy is to remove ‘manipulated media’ – with the exception of parodies. YouTube’s policy on ‘deceptive practices’ prohibits doctored content that’s misleading or may pose serious risks, and TikTok removes ‘digital forgeries’ – including inaccurate health information – that are misleading and cause harm. Reddit removes media that impersonates individuals or entities in a misleading or deceptive manner, but has also created an exemption for satire and parody. With the volume and sophistication of deepfakes skyrocketing, it’s unclear, however, how social networks will be able to keep up with enforcing these policies. One thing they could do is automatically label deepfakes, irrespective of whether or not the deepfakes cause harm, so that they can at least create more awareness.

Spotting super-realistic deepfake images

Researchers at the University of Buffalo have come up with an ingenious new tool for spotting super-realistic deepfakes. In their paper, the researchers explain how they created a method for distinguishing authentic images from those generated by deepfake technology, and they basically do this by looking closely at the eyes of the person in the image. What the researchers found is that the reflections in both eyes of the person in an authentic photograph are usually identical as a result of the same light environment. This is, however, mostly not the case when it comes to doctored images. Their technology, when tested on deepfake-generated images, managed to pick out deepfakes in 94 per cent of cases. The tech is most accurate, however, when used on photos taken in the portrait setting, which is generally the preferred option when shooting close up portrait photographs.

Genuine presence assurance

Being able to verify that the person you see in online content is authentic is critical in the fight against the misuse of deepfakes, and iProov Genuine Presence Assurance can do exactly that. iProov’s system uses biometric scans that can help identify whether the person in question is indeed a live human being and not a photo, video, mask, deepfake, or other replay or presentation attempting to spoof a (biometric) security system. The system works on mobile devices, computers, or at unattended kiosks, and is used by organisations around the world, such as the UK’s NHS. The health service has chosen iProov’s biometric facial authentication to improve users’ remote onboarding experience. Thanks to iProov’s Flashmark facial verification technology, users can log in to the NHS app remotely and securely to make appointments, access medical records, and order prescriptions. The process involves submitting an ID photo and positioning one’s face on the screen. After a short sequence of flashing colours, the user’s identity is verified and the NHS app can be accessed.

Antivirus for deepfakes

Sensity, an Amsterdam-based company that develops deep learning technologies for monitoring and detecting deepfakes, has developed a visual threat intelligence platform that uses the same deep learning processes used to create deepfakes, combining deepfake detection with advanced video forensics and monitoring capabilities. The platform – a kind of antivirus for deepfakes, if you will – monitors over 500 sources across the open and dark web, where the likelihood of finding malicious deepfakes is high. It then alerts users when they’re watching something that’s potentially AI-generated synthetic media, providing detailed severity assessments and threat analyses. Sensity also enables you to either submit URLs or upload your own image and video files. It then analyses them to detect the latest AI-based media manipulation and synthesis techniques, including fake human faces in social media profiles, dating apps, or financial services accounts online. Sensity also offers access to the world’s most comprehensive deepfake database and other visual media targeting public figures, including insights on most targeted industries and countries.

The future of fake and other considerations

Pandora’s box has opened, and it looks like the competition between the creation and detection and prevention of deepfakes will become increasingly fierce in the future, with deepfake technology not only becoming easier to access, but deepfake content easier to create and progressively harder to distinguish from real. Deepfakes will continue to evolve and spread further, and issues like the lack of details in the synthesis will be overcome, and with lighter-weight neural network structures and advances in hardware, training and generating time will be significantly reduced. We’ve already seen new algorithms that can deliver increasingly higher levels of realism and run in near real time. According to experts, GANs (generative adversarial networks) will be the main drivers of deepfakes development in the future, and these will be near-impossible to distinguish from authentic content.

And while the use of deepfakes for good is increasing rapidly in sectors like entertainment, news, and education, these developments will, conversely, also introduce even more serious threats to the public, including increasing criminal activity, the spread of misinformation, synthetic identity fraud, election interference, and political tension. Another aspect to consider is that deepfakes mess around with agency and identity. You can make someone do something that they’ve never done, using someone’s photo – for which the owner has probably never given his or her permission. And once a video is online, you lose all control over how it is used or interpreted.

Going forward, in order to minimise deception and curb the undermining of trust, technical experts, journalists, and policymakers will play a critical role in speaking out and educating the public about the capabilities and dangers of synthetic media. And if we, the public, can educate ourselves to only trust content from reputable sources, we might find that the good uses of deepfakes could actually outweigh the bad. With increased public awareness, we could learn to limit the negative impact of deepfakes, find ways to co-exist with them, and even benefit from them in the future.