- Growing sophistication and professionalism enable cybercrime

- State sponsorship is a major issue: North Korea and Russia

- What will the future bring?

- What needs to be done?

“Cybercrime is relentless, undiminished, and unlikely to stop. It is just too easy and too rewarding, and the chances of being caught and punished are perceived as being too low.” That’s a pretty direct warning from James Lewis, the director and senior fellow of the Technology and Public Policy Program at the Center for Strategic and International Studies. And unfortunately, he’s right.

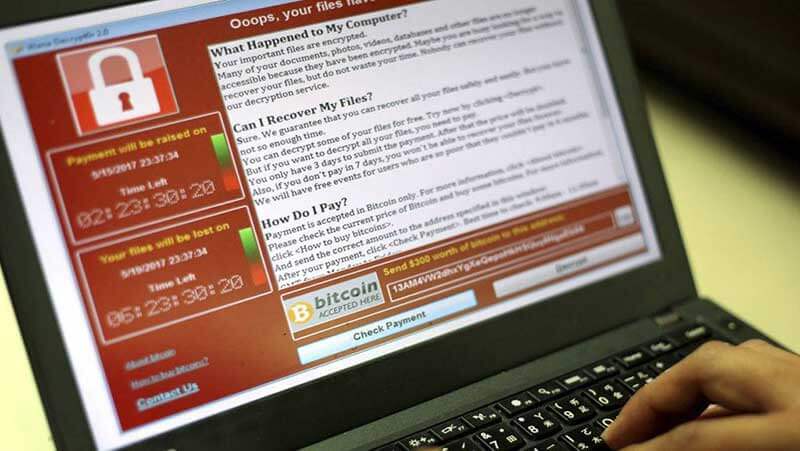

2017 was a banner year for the bad guys. As Alcor reports, ransomware was a real problem, with NotPetya/ExPetr, WannaCry, and Bad Rabbit as leading examples of malicious attacks. Josh Fruhlinger, a security expert writing for CSO, explains that “Ransomware is a form of malicious software (or malware) that, once it’s taken over your computer, threatens you with harm, usually by denying you access to your data. The attacker demands a ransom from the victim, promising — not always truthfully — to restore access to the data upon payment.” It’s only one kind of cybercrime, but unfortunately one that’s growing in popularity. We see it as the biggest cyber threat of 2018, and we’re concerned about just how widespread these attacks have become.

The CSIS/McAfee report makes this worryingly clear. “A good estimate is that two-thirds of the people online— more than two billion individuals—have had their personal information stolen or compromised,” it states. “One survey found that 64% of Americans had been victims of fraudulent charges or loss of personal information. Cybercrime is front-page news because it touches everyone.”

Growing sophistication and professionalism enable cybercrime

The reasons for its popularity among high-tech criminals are easy to understand. As Lewis writes, “Cybercrime also leads in the risk-to-payoff ratio. It is a low risk crime that provides high payoffs. A smart cybercriminal can make hundreds of thousands, even millions of dollars with almost no chance of arrest or jail.” That’s because these criminals are growing more sophisticated, acting in concert across global networks and ‘cybercrime centres’ like North Korea and Russia. And with access to anonymised, secure payment systems like Bitcoin, it’s very hard to catch them in the act. “Bitcoin has long been the favored currency for darknet marketplaces, with cybercriminals taking advantage of its pseudonymous nature and decentralized organization to conduct illicit transactions, demand payments from victims, and launder the proceeds from their crimes,” Lewis says.

And unfortunately, cybercrime like ransomware pays really well. While corruption and drug trafficking involve larger amounts of money, cybercrime’s haul is nothing to sneer at. According to the CSIS/McAfee report, “cybercrime may now cost the world almost $600 billion, or 0.8% of global GDP”.

State sponsorship is a major issue: North Korea and Russia

That’s huge. Worse still, in some cases, these cybercriminals aren’t just operating with a free-hand; they’re actually state-sponsored. At the very least, this shields them from the fear of investigation and punishment. But sometimes this also means real support, and backed by government resources and access to talent, these attacks can be crippling.

For countries like North Korea, already a pariah state and struggling to keep a sinking economy afloat, getting a piece of the cybercrime action is an opportunity not to be missed. With economic sanctions in place, professional attacks backed by the government can bring in desperately needed cash. Dorothy Denning, a recognised expert in security and analysis, observes that, in a country that restricts internet access to the elite, “it seems unlikely the country has hackers who operate independent of the government”. The threat they offer is coordinated, organised, and state-sponsored: these hackers “work primarily for the General Bureau of Reconnaissance or the General Staff Department of the Korean People’s Army”, she writes. And though sometimes sloppy, the scale of the thefts they attempt is staggering. In 2016, for instance, “the regime came close to stealing US$951 million from the Bangladesh Central Bank over the global SWIFT financial network”, she reports.

Nearly a billion dollars is strong motive to sponsor cybercrime, but that’s not the only reason for states to support ransomware and denial of service (DOS) attacks. Geopolitical battles are increasingly fought digitally and with plausible deniability, making cybercrime a front-line weapon. Russia has been suspected of supporting a variety of attacks in Ukraine, each designed to weaken support for its leaders and render its public services ineffective. Consider, for example, the recent ransomware and distributed denial of service (DDOS) attacks on Ukraine’s national postal service, Ukrposhta. These were strikingly similar to the hacking of Kiev’s power grid in 2015, a coordinated assault linked to computers with Russian IP addresses, suggesting but not proving that this was state-sponsored. And what has security experts like Robert Lee worried is that “nothing about it is unique to Ukraine … They’ve built a platform to be able to do future attacks”. Everyone’s at risk.

What will the future bring?

Ransomware is far from the only kind of cybercrime, but it’s the fastest growing because it’s the most lucrative. And it’s becoming big business as Ransomware-as-a-Service (RaaS) takes off. This frightening trend involves the professionalisation of high-tech crime and its sale as a service. As Lewis explains, “Instead of a single actor or group writing ransomware and distributing it themselves, the RaaS model allows for authors to set up platforms where ‘affiliates’ can deploy it to their own list of targets. Typically, the authors take a cut of the resulting ransoms, though some may charge an up-front fee or sell blocks of time to access the command and control servers running the campaign.”

And as Swati Khandelwal reports for The Hacker News, new RaaS threats are shockingly inexpensive. As she writes, “A new credential stealing malware that targets primarily web browsers is being marketed at Russian-speaking web forums for as cheap as $7, allowing anyone with even little technical knowledge to hack as many computers as they want.

Dubbed Ovidiy Stealer, the malware … initially appeared just last month but is being regularly updated by its Russian-speaking authors and actively adopted by cyber criminals.” That should frighten you – at that cost, anyone can afford to get into the ransomware racket.

That’s why we expect to see a sharp increase in ransomware attacks in 2018, and we’re pretty sure they’ll grow in frequency, number, and cost.

What needs to be done?

Experts think some pretty basic measures can help. Most ransomware attacks don’t start with high-sophistication. Instead, we’re almost willing victims as we open and download suspicious files, respond to phishing inquiries, or otherwise expose ourselves to unnecessary risks. Even just updating your operating system and browser can help. As Lewis notes, “Protection against most cybercrimes does not require the most sophisticated defenses.”

But international cooperation is vital, too. State sponsors need to be punished, and more effort needs to be made to end ‘state sanctuaries’ for cybercriminals. That’s not all that likely, so for the near future, it’s best to tighten personal security and make sure that you only open and download files from trusted sources.

We hope we’re wrong about 2018, and we’ll be watching.