- The discovery of CRISPR revolutionised genetics research

- The lack of a universal regulatory framework

- Chinese scientist claims he created the first genetically edited babies

- Stephen Hawking was concerned that genetic engineering could create a new race of superhumans

- Superhumans – a plausible idea or pure science fiction?

- Endless possibilities

Human beings are the product of millions of years of evolution. We’re one of the most complex forms of life in the known universe, with some amazing abilities at our disposal. But, at the same time, we’re also very fragile and vulnerable, susceptible to all kinds of diseases that can cut our lives tragically short. For years, scientists have been looking for ways to improve upon this original, natural design and make humans stronger, healthier, and better. And they’ve been successful to a certain degree, eradicating many diseases and significantly extending the human lifespan.

Throughout that time, one idea in particular has occupied scientists’ minds: using gene editing to identify and correct genetic mistakes in our DNA that could potentially lead to disease. However, although several gene editing techniques have been developed over the years, they all proved very complicated, extremely expensive, and rather limited in scope. But then, in 2012, CRISPR appeared — and changed everything, forever.

The discovery of CRISPR revolutionised genetics research

The CRISPR system is a powerful gene editing tool that allows scientists to target a specific DNA sequence and remove genes that cause a disease, or replace them with new, healthy genes. While incredibly promising, CRISPR is a relatively new technology, and we still don’t know enough about how it works or the exact side-effects. For example, we don’t know whether the changes are confined to the targeted DNA sequence or if they’ll cause unintended effects elsewhere in the genome. “Deleting a single gene may not only alter how other genes are going to function but also may alter the overall behavior of the cell and the phenotype of [the] organism,” says Mazhar Adli, a geneticist at the University of Virginia School of Medicine.

That’s why the use of CRISPR on humans is currently only allowed for treating deadly diseases, and only in those cases where there’s no danger of the changes being passed on to future generations. With germline editing, which is the altering of genes in sperm, eggs, or embryos, the altered sequence can be passed on to the next generation. This is why this type of procedure has been banned in countries around the world, except for research purposes. “In germline gene transfer, the persons being affected by the procedure — those for whom the procedure is undertaken — do not yet exist. Thus, the potential beneficiaries are not in a position to consent to, or refuse, such a procedure,” explains the National Human Genome Research Institute (NHGRI). Unfortunately, that hasn’t stopped some people.

The lack of a universal regulatory framework

At this moment, there isn’t a single international organisation or a set of universally recognised rules that regulate human genome modification. Instead, each country has to come up with its own rules and guidelines. In the United States, for instance, germline editing is only allowed if done with private funding, but selling the treatment to US citizens requires FDA approval. Editing the genome of a human embryo is banned in the United Kingdom, unless given explicit approval by the Human Fertilisation and Embryology Authority (HFEA), which regulates fertility treatment and embryo research. All in all, human germline modification is banned in more than 40 countries around the world, including France, Germany, Italy, Spain, the Netherlands, Brazil, Canada, and Australia.

In China, however, gene editing isn’t only allowed, but also heavily backed by the government, which is reportedly investing $300 billion in gene editing technologies. Over the last four years, China’s Natural Science Foundation has funded more than 300 CRISPR initiatives, putting the country at the cutting edge of this type of research. In 2015, Chinese scientists used gene editing technology to modify non-viable human embryos for the first time, followed by the world’s first CRISPR human trial in 2016, in which the revolutionary technique was used to treat patients with aggressive lung cancer. But there’s more.

Chinese scientist claims he created the first genetically edited babies

In November 2018, the Chinese scientist He Jiankui shocked the world when he revealed that he used CRISPR to create the world’s first genetically edited babies. Aided by his former graduate advisor, Rice University physicist and bioengineering professor Michael Deem, He claims he used the gene editing tool to alter human embryos for seven HIV-positive couples during fertility treatments. He did this by removing a gene called CCR5 that’s known to aid the development of HIV. He hoped that this would make the babies resistant to the disease. So far, one of the seven pregnancies was successful, resulting in the birth of healthy twin girls, Lulu and Nana.

While nobody has been able to verify He’s claims yet, the announcement was widely condemned by the science community. “It’s unconscionable … an experiment on human beings that is not morally or ethically defensible,” says Dr. Kiran Musunuru, a University of Pennsylvania gene editing expert and editor of a genetics journal. One of the problems with what He did is that the CCR5 gene does more than aid the development of HIV, including helping white blood cells function properly. Deleting it could make a person more susceptible to other viruses, such as the West Nile virus or the flu. And since we already have very effective ways of preventing and treating HIV infections, the medical risks far outweigh any potential benefits.

According to the Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS (UNAIDS), there were 1.8 million children under the age of 15 living with HIV in the world in 2017, the majority of whom were infected during pregnancy, childbirth, or breastfeeding through mother-to-child transmission (MTCT). However, thanks to improved access to antiretroviral therapy for women living with HIV, the number of new HIV infections among children has declined by 35 per cent in recent years, from 270,000 in 2010 to 180,000 in 2017. Perhaps, rather than trying to make children immune to the disease through potentially risky gene editing, we should focus on making sure that every person living with HIV has access to antiretroviral medication to prevent future infections and manage existing ones.

Stephen Hawking was concerned that genetic engineering could create a new race of superhumans

Some people, however, believe that gene editing could have even more sinister consequences. Shortly before his death, the great physicist Stephen Hawking wrote an essay in which he expressed fears that this technology may eventually lead to the creation of a new race of superhumans that could destroy the rest of humanity. “I am sure that during this century, people will discover how to modify both intelligence and instincts such as aggression,” writes Hawking. “Laws will probably be passed against genetic engineering with humans. But some people won’t be able to resist the temptation to improve human characteristics, such as memory, resistance to disease and length of life.”

Hawking was concerned that this technology would only be available to the wealthy, who would be able to enhance their genetic makeup, while the rest of us would have to go on hampered by our imperfections. “Once such superhumans appear, there will be significant political problems with unimproved humans, who won’t be able to compete,” Hawking continues. “Presumably, they will die out, or become unimportant. Instead, there will be a race of self-designing beings who are improving at an ever-increasing rate.”

Superhumans – a plausible idea or pure science fiction?

Evil scientists bent on taking over the world with an army of genetically modified super-soldiers are a well-established science fiction trope and you’ve probably seen dozens of movies on the topic. But could it actually happen? After all, as brilliant as he was, Hawking was a physicist, not a geneticist, so gene editing wasn’t exactly his area of expertise. Biologist and director of the Plant Transformation Facility at Cornell University, Matthew Willmann, believes that, while theoretically possible, this scenario is highly unlikely. “Could it happen? Yeah. But there’s a lot going on to prevent that from happening,” he says. There are already strict laws and ethical codes in place to regulate gene editing. Circumventing these without attracting attention would be almost impossible. Furthermore, genetics is far too complicated and the whole process takes far too long for it to work the way it does in movies.

Endless possibilities

But let’s say for the sake of argument that there are no legal or ethical concerns. In addition to helping us eradicate diseases like HIV or cancer, what else could CRISPR theoretically do? For instance, Chinese scientists recently identified four genetic mutations of the CASC5 gene associated with a larger brain size, while a specific variant of the HMGA2 gene was also previously linked with the size of the brain and higher intelligence. A 2017 study published in Nature Genetics, which analysed the genomes of more than 78,000 individuals, identified 52 genes associated with human intelligence.

According to the researchers, though, none of the genes identified contributed more than a small fraction of a percentage point to intelligence, which means that they can’t be the only ones that influence this trait, and further research is required before we can better understand how intelligence is formed in the brain and whether it’s purely genetic. However, these discoveries open the door to one day using CRISPR to increase the intelligence of an embryo. That’s not all, though. In theory, we could also use the same approach to enhance almost any other physiological trait, including bone density, muscle strength, resistance to extreme temperatures or radiation, psychological resilience, and even aging.

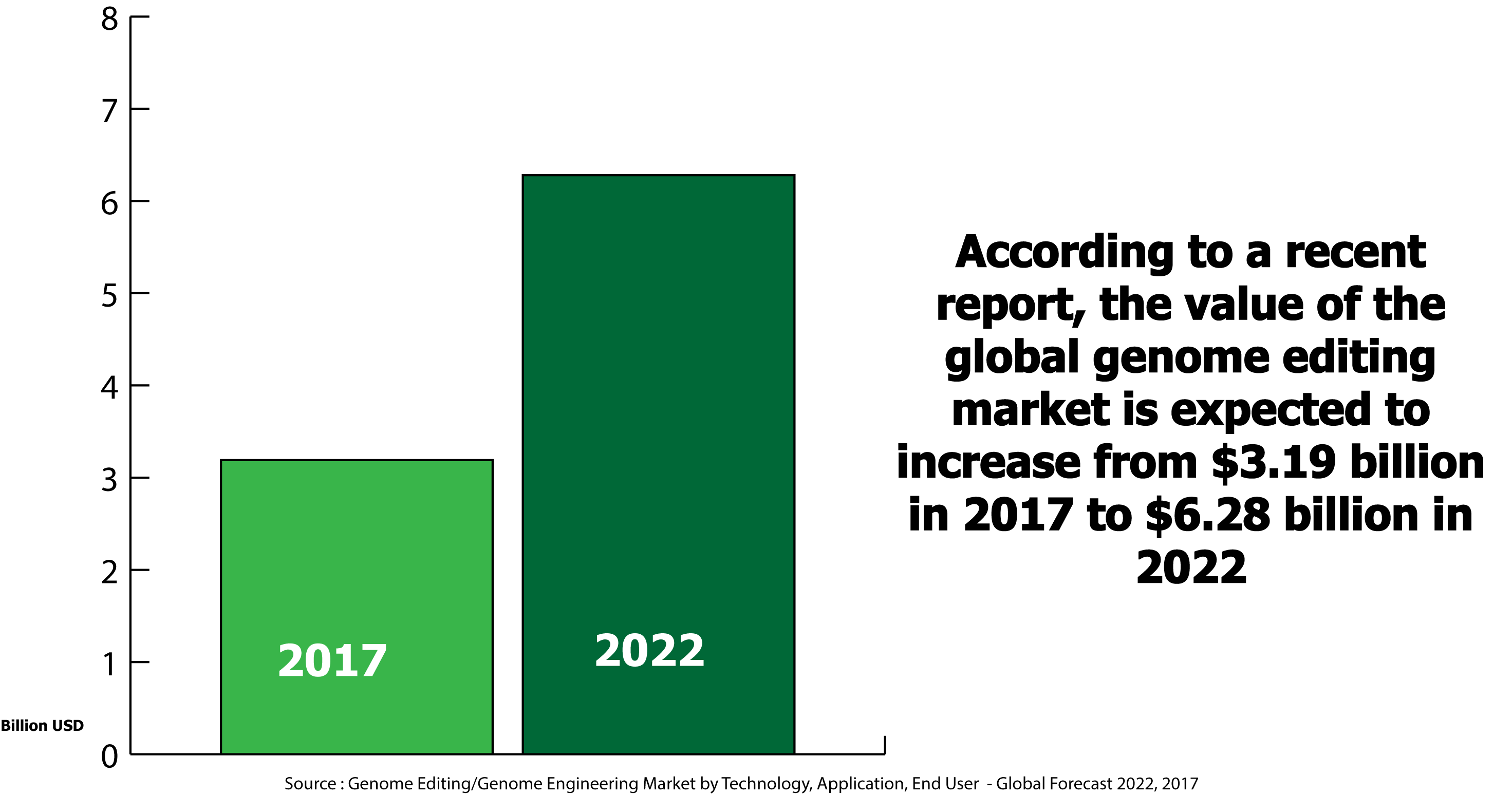

Despite concerns and doomsday predictions, gene editing isn’t going away anytime soon. According to a recent report, the value of the global genome editing market is expected to increase from $3.19 billion in 2017 to $6.28 billion in 2022.

There are currently more than 2,800 ongoing gene therapy clinical trials around the world, targeting a wide variety of diseases, including cancer, sickle cell anemia, and muscular dystrophy. Major pharmaceutical companies, such as Novartis, GlaxoSmithKline, Bayer, Pfizer, and Merck have also recognised the business opportunity offered by this field and are investing heavily in the small companies that are running these trials.

The discovery of CRISPR brought genetic engineering into the mainstream and raised a myriad of safety and ethical concerns. Although it’s highly unlikely that gene editing could lead to the creation of superhumans, this scenario can’t be dismissed outright and remains a distinct theoretical possibility. This is why we need to tread carefully with gene editing technologies like CRISPR. It’s an incredibly promising technology, but we still don’t know enough about it to justify its use on humans. Until that changes, gene editing is likely to remain a highly regulated field, especially in germline editing, which has been banned in more than 40 countries around the world. Research will continue, though, backed by major pharmaceutical companies, and should provide the answers we’re looking for in time.