- Bioprinting is gaining momentum

- Making the new tech available to everyone

- Startups are joining forces to conquer new frontiers

- Scientists are making steady progress

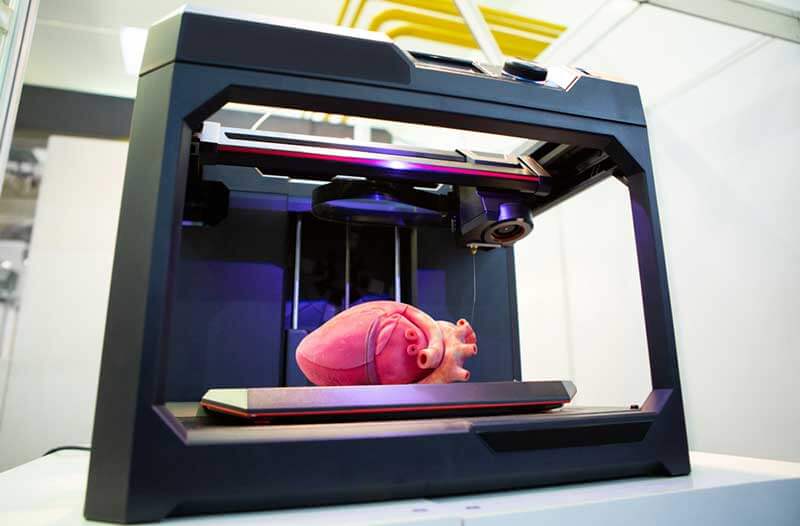

Printing human organs from scratch might seem a bit farfetched at first, but thanks to steady improvements in bioprinting, it might become possible sooner than most people think. The value of the global bioprinting market is set to reach €2.1 billion by 2025, its growth mostly fuelled by cosmetics and pharmaceutical companies that are abandoning animal testing and turning to more humane alternatives such as bioprinted human skin. But the main goal of bioprinting is much bigger – finding a way to produce fully functioning human organs. If successful, 114,154 people in the US alone who need a life-saving organ transplant could be saved. This is great news, since many people on the transplant waiting list never even receive an organ, as 20 people die each day waiting for a transplant.

Until recently, solving this problem proved to be a rather elusive goal, as existing technology simply wasn’t capable of printing blood vessel systems that are essential for the survival and growth of tissue. Additionally, less than two years ago, there were no standardised ‘bioinks’ used by 3D printers. Many of these problems are now being resolved by promising bioprinting startups such as Cellink and Prellis Biologics, the meteoric growth of which proves that both investors and customers are eagerly awaiting a breakthrough in this industry.

Bioprinting is gaining momentum

The steady rise of bioprinting can be partially attributed to the EU’s decision to ban animal testing for cosmetics in 2013. Instead of testing the effects of new beauty products on animals, many producers and their suppliers are now doing it on bioprinted skin. For instance, L’Oréal partnered with the US startup Organovo, one of the bioprinting pioneers, to devise ways to manufacture cheaper ‘fake’ skin to curb public concern over animal cruelty. Similarly, the French startup Poietis launched a bioprinted human skin model called Poieskin, which allows customers to analyse “cosmetic ingredients and finished products”.

Pharmaceutical testing of new drugs also benefits from bioprinted tissues that resemble those found in organs like the heart or liver, and into which scientists can inject particular chemical components to observe reactions. This not only reduces testing on animals, but also provides scientists with better insights into how the human body might react to a particular medicine. And as for the transplant of 3D-printed organs, Bruno Brisson, a co-founder of Poietis, predicts that the skin will be the first organ to be transplanted within three to five years.

Making the new tech available to everyone

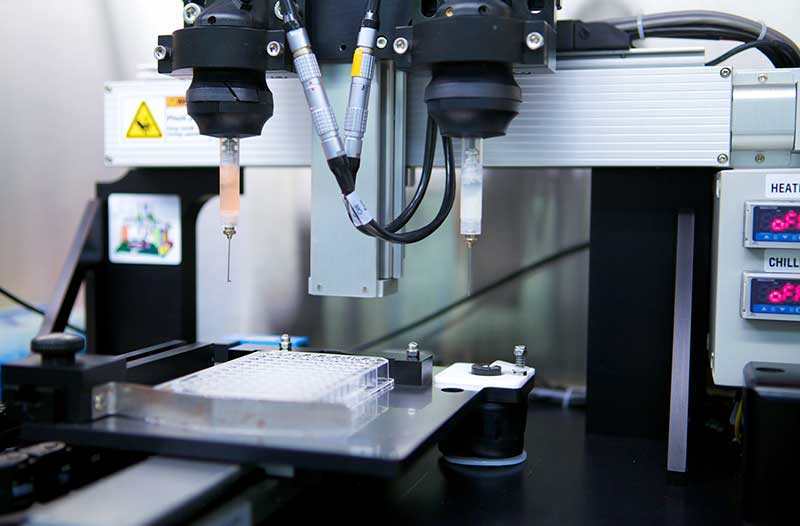

Meanwhile, the Swedish startup Cellink has partnered with CTIBiotech, a French medtech company, to 3D print replicas of tumors that can be used to test the efficacy of new treatments. Cellink will provide 3D printers and bioink that will then be mixed with the patients’ cancer cells. Cellink’s CEO, Erik Gatenholm, explains that “You will be able to see how a tumor grows and how it would respond to different treatments. It’s a very relevant and a realistic model for research.” Cellink also produces noses, ears, and skin for drugs and cosmetics testing, but its biggest contribution to bioprinting lies in the standardisation of bioinks.

Just two years ago, many researchers across the world had to mix their own bioink when they wanted to print human tissue. That was expensive, time-consuming, and slowed down the advancement of bioprinting. Gatenholm saw a business opportunity and developed a range of bioinks that can be used to fabricate bone, skin, muscle, and a number of other types of cells. He’s also developed affordable 3D printers, some of which cost under $5,000. The company, which was created in 2016, was already profitable by 2017 and even went public, raising funds in an initial public offering (IPO). But the best is yet to come, and its partnership with Prellis Biologics, a US human tissue engineering company, opens the door for new and exciting projects.

Startups are joining forces to conquer new frontiers

Existing bioprinting technology limits scientists to “printing tissue no thicker than a dollar bill”. That’s useful for testing cosmetics and drugs, but not thick enough to be a building block for fully functional organs. The main reason is that 3D printers aren’t capable of producing tiny, yet highly complex blood vessel systems that consist of many types of veins and arteries that deliver blood and take away waste matter. This function is essential for the growth and thickness of human tissue and for us to be able to 3D print fully functioning organs.

The Holograph-X Bioprinter, made by Cellink and Prellis Biologics, is hailed as a potential solution to this problem. It relies on Prellis Biologics’ proprietary 3D laser-based printing technology that produces “fine capillaries, that deliver nutrients to cells, and scaffolds, that help support the growth of cells into a 3D tissue”. In other words, the printer could actually produce tissue thick and complex enough to create functional organs. The role of Cellink in this project is related to the “design of the system, user interface development, and sales of the system, ink and consumables”. The price of the Holograph-X Bioprinter, which will hit the market in 2019, is a whopping $1.2 million. But if the machine delivers on its promise, it may well be worth the price.

Scientists are making steady progress

Bioprinting is a cutting-edge technology that sometimes seems like it’s beyond the realm of possibility. Yet, year after year, scientists are making steady progress, from ‘fake’ skin that helps the cosmetics and pharmaceutical industries to cancer tissue used for medicine testing. And with new technologies that could potentially print even tiny capillaries, 3D-printed human organs appear less and less like a distant future and more like a viable plan.