- Artificial intelligence will probably be nothing like us

- Would human morality apply to it? And if so, which one?

- Two bad examples of how to teach a machine moral reasoning

- Treating AI like a child might help – but that comes at a steep price

Futurists have been predicting the rise of self-aware artificial intelligence for decades, prompting Thomas Hornigold to quip that AI has been just 20 years away since 1956. And while tongue-in-cheek, he’s not far off the mark. Chasing AI – real machine intelligence – is like running down a motorcycle on foot: the farther you run, the farther the motorcycle retreats.

We’ve come a long way toward creating this new kind of mind, but we still have miles to go. And before we get there, we need to consider what the birth of a new kind of being might mean, how it might shape us, and how we might shape it, too. Will we want to give an artificial mind a sense of human morality? Indeed, can we?

This is a pressing question, and like most such issues, the weight pushing it on us is fear. We’re worried because some sharp people have warned us that we should be. No lesser luminary than Stephen Hawking cautioned that when sufficiently advanced machines take over their own evolution, some scary unintended consequences could follow. “The development of full artificial intelligence could spell the end of the human race,” he told the BBC. What happens, for instance, when a machine mind that’s developed itself far beyond our puny powers decides that humanity is a problem, an impediment, or even a threat?

Unfortunately, most of the people working on AI aren’t a whole lot of help with these questions. From confusions about what morality is and can be, to wild assumptions about the nature of machine intelligence, there isn’t a lot of clarity. To be fair, these aren’t easy answers to give. Here, we’ll try to untangle some of these issues and see if we can shed some light on a possible next step.

Artificial intelligence will probably be nothing like us

A good place to start might be to consider just what a machine intelligence might be. It’s not helpful to begin with worries about artificial intelligence – at least not those worries – until we consider just how alien machine life might be. Will a sufficiently alien machine intelligence even care to be humanity’s overlord? Here, as in so many forays into the future, science fiction can be a help. Stanisław Lem’s brilliant Solaris, for example, explores humanity’s encounter with a truly alien mind. He presents his reader with a being so unlike us that even when we recognise its intelligence – its rational exploration of the characters is unmistakable – communion with it is impossible.

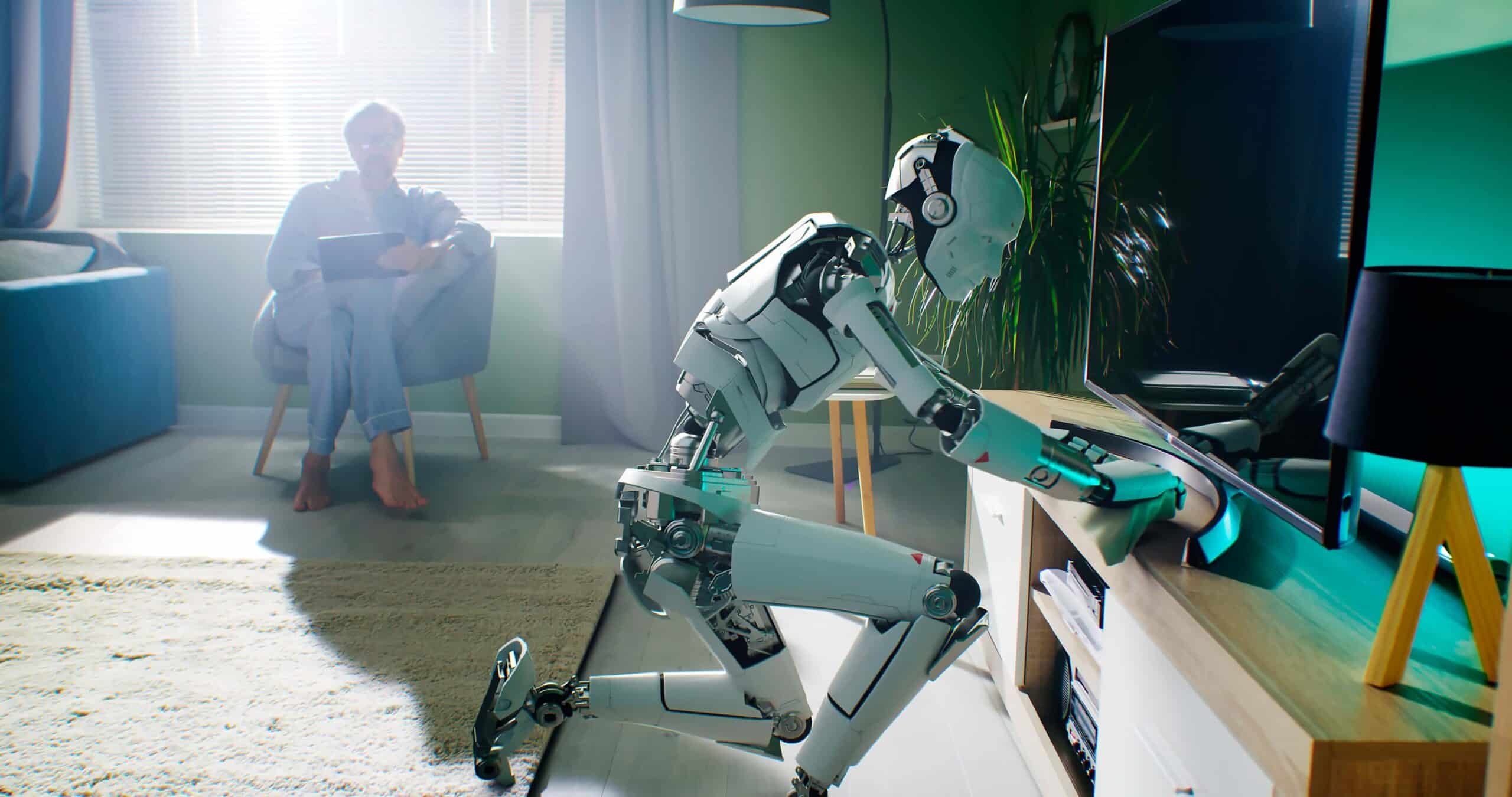

That’s a useful way to begin considering AI. Unencumbered by the biological imperatives to grow, reproduce, and survive, we might find a machine mind’s reasons for existing hopelessly alien. In fact, perhaps before we worry about what such an entity might do to us, we ought to ask if it will even bother interacting with humanity. Indeed, if it’ll even bother continuing to exist. Most of us don’t talk to our homes, though we live and love in them. Might a machine intelligence interact with us, live with us, use us – and not find us worthy of conversation? Stranger still, artificial intelligence won’t be born with the drive to live – or concerns about the ethics of suicide. Free from existential questions, might it choose not to be the moment after it flashes into being?

We need to approach the possibilities with imagination; an alien mind might be incomprehensible to us. Consider AlphaGo, a game-playing AI that befuddled experts with its winning ‘Move 37’. Trained to play the ancient game Go, it defeated the best human opponent with tactics so unconventionally effective that onlookers were simply lost. That’s a trivial example, but instructive nonetheless. Even when we’re playing the same game, governed by a well-understood set of rules, rudimentary AI can prove itself impossible to understand. It would be a big mistake to imagine advanced machine intelligence in our own image. If it’s alien enough, the way we understand right and wrong may not apply.

Would human morality apply to it? And if so, which one?

But let’s say that a self-aware machine was sufficiently like us that we could communicate and share our goals and plans. What then? Ought we teach it human morality?

We might wish that it was that simple. An initial problem is that there’s no general consensus about which morality to teach human beings, let alone machine minds. From the ethical realism of Plato to the virtue ethics of Aristotle, from the categorical imperatives driving Kantian moral reasoning to the hedonic calculations of Bentham, there are good arguments to be made for a variety of moral positions. And as any professor of ethics will explain, intelligent people can and do disagree about the answers to any but the most mundane questions. That murder should be prohibited is tautologically true, but can one kill in self-defense is another question entirely. So, too, for pretty much any actual moral question, where the colours in play are almost never black and white but rather nearly indistinguishable shades of grey.

That is, before we could begin to teach a machine morality, we’d need to decide which morality to teach it. And the people working on AI – the actual scientists and engineers behind the projects – are bad at thinking these issues through. Two particularly awful approaches currently being investigated would be laughable if the stakes weren’t so high.

Two bad examples of how to teach a machine moral reasoning

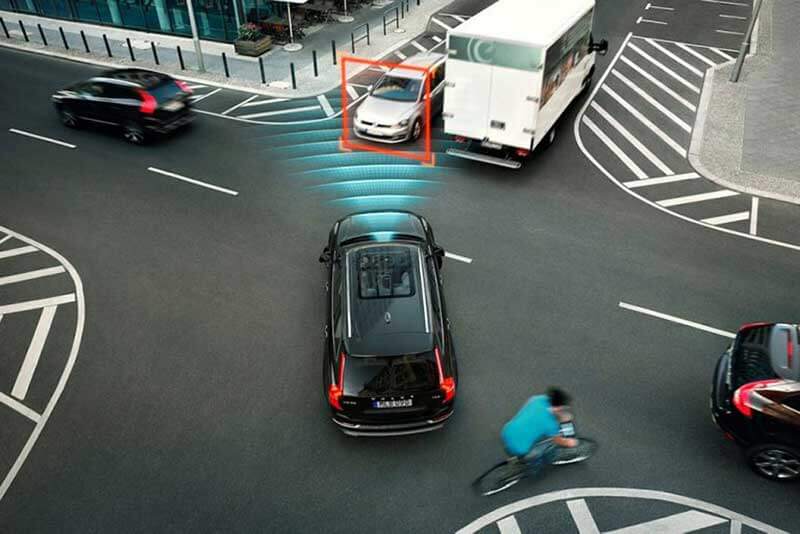

For instance, researchers from MIT are interested in crowdsourcing morality “to effectively train machines to make better moral decisions in the context of self-driving cars”. Basically, this approach collects answers from internet users related to ethical questions a self-driving car might encounter. Should it swerve to avoid a dog and thereby kill the passenger? Should it prioritise killing one sort of person – a homeless man – over another – a young athlete? By offering people the chance to weigh-in on these questions, the researchers hope to arrive at a crowd-sourced moral consensus.

This is an amazingly terrible idea for several reasons. People are bad at ethical reasoning, using their gut far more often than their head. And since the goal of teaching autonomous vehicles ethics is presumably to do better than we can, teaching them to imitate our limitations is unwise. Worse still, as the Tay experiment demonstrated, crowdsourcing morality quickly resulted in teaching AI to adore Hitler and spew racist venom. You wouldn’t turn to Reddit for your child’s moral education, so why would that be any better for ‘young’ machine intelligence?

In another example of why we need to begin this conversation in earnest, researchers from the School of Interactive Computing at the Georgia Institute of Technology have turned to fiction to outsource moral education for AI. The program, called Quixote, is animated by the idea that by having machines learn from the protagonists of books, we can better teach them to be good.

Anyone familiar with literature will immediately recognise this as the naive idea that it is. While the scientists behind this project “believe that AI has to be enculturated to adopt the values of a particular society, and in doing so, it will strive to avoid unacceptable behavior”, one wonders if they’ve read things like Nabokov’s Lolita, any of Shakespeare’s plays, or even the program’s eponymous Don Quixote. As John Mullen notes for the Guardian, “a literary work may be morally instructive without having a single character that you would ever want to imitate.” Perhaps ironically, this realisation leaves us wondering if Mark Riedl and Brent Harrison, the scientists behind this project, aren’t as intoxicated by romanticism as Quixote himself.

So what should we do?

Treating AI like a child might help – but that comes at a steep price

A reasonable first step has been proposed by Regina Rini, assistant professor and faculty fellow at the New York University Center for Bioethics, and an affiliate faculty member in the Medical Ethics division of the NYU Department of Population Health. We need to begin by recognising that human morality is inescapably human. Artificial intelligence probably won’t be a lot like us, and to the degree that a machine mind is alien, our moral notions won’t be a great fit. And to complicate an already complicated problem, if we accept that an artificial intelligence is a being, a self-aware entity with rights of its own, and thus presume limits on our freedom to do with it what we like, we’ll need to accept that agency, even when we disagree with its choices. Make no mistake: its moral calculus will probably be wildly different to our own, reflecting the fact that it isn’t like us. And that presents a unique challenge.

As Rini writes for Aeon magazine: “… we should accept that artificial progeny might make moral choices that look strange. But if they can explain them to us, in terms we find intelligible, we should not try to stop them from thinking this way. We should not tinker with their digital brains, aiming to reprogramme them. We might try to persuade them, cajole them, instruct them, in the way we do human teenagers. We should intervene to stop them only if their actions pose risk of obvious, immediate harm. This would be to treat them as moral agents, just like us, just like our children. And that’s the right model.”

This implies, of course, a great deal of responsibility on our part, a role that will at the very least demand us to function in loco parentis. Most of us think through the consequences of having children, talk to our partners about our expectations, and discuss everything from parenting techniques to our hopes and dreams for our kids. It’s time for us to do something similar with AI, before it really is too late.