- The problem with conventional image tech

- Seeing inside a patient – without a scalpel

- ProjectDR moving forward

If you’ve been keeping up with tech, you know that augmented reality (AR) has proven its usefulness beyond games like Pokémon GO. Because it allows information to be displayed over the real world, it’s a fantastic tool for many applications. From real estate to engineering, AR is showing its promise. And this tech is here, now – not a promise for the future. With a HoloLens headset, for instance, technicians working for elevator manufacturer ThyssenKrupp can take a look at the inner workings of an elevator and access its repair history, improving service and ensuring everyone’s safety.

That’s not just cool – that’s clever! But a new pilot program at the University of Alberta wants to bring that same digital magic to the operating room, allowing surgeons to see inside their patients before they make the first incision. Ian Watts and Michael Fiest, graduate students in computer science, have developed a system they call ProjectDR, and if it works as planned, it may revolutionise medical teaching and patient care.

The problem with conventional image tech

To see inside patients now, medical professionals use techniques like x-rays, computed tomography (CT) scans, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), and ultrasound. These can reveal hard structures like bones, allowing radiologists to see a broken leg, for instance, but they can also reveal soft organs like your liver or brain. Together, they provide physicians with the tools they need to see inside you, make diagnoses, and plan surgery.

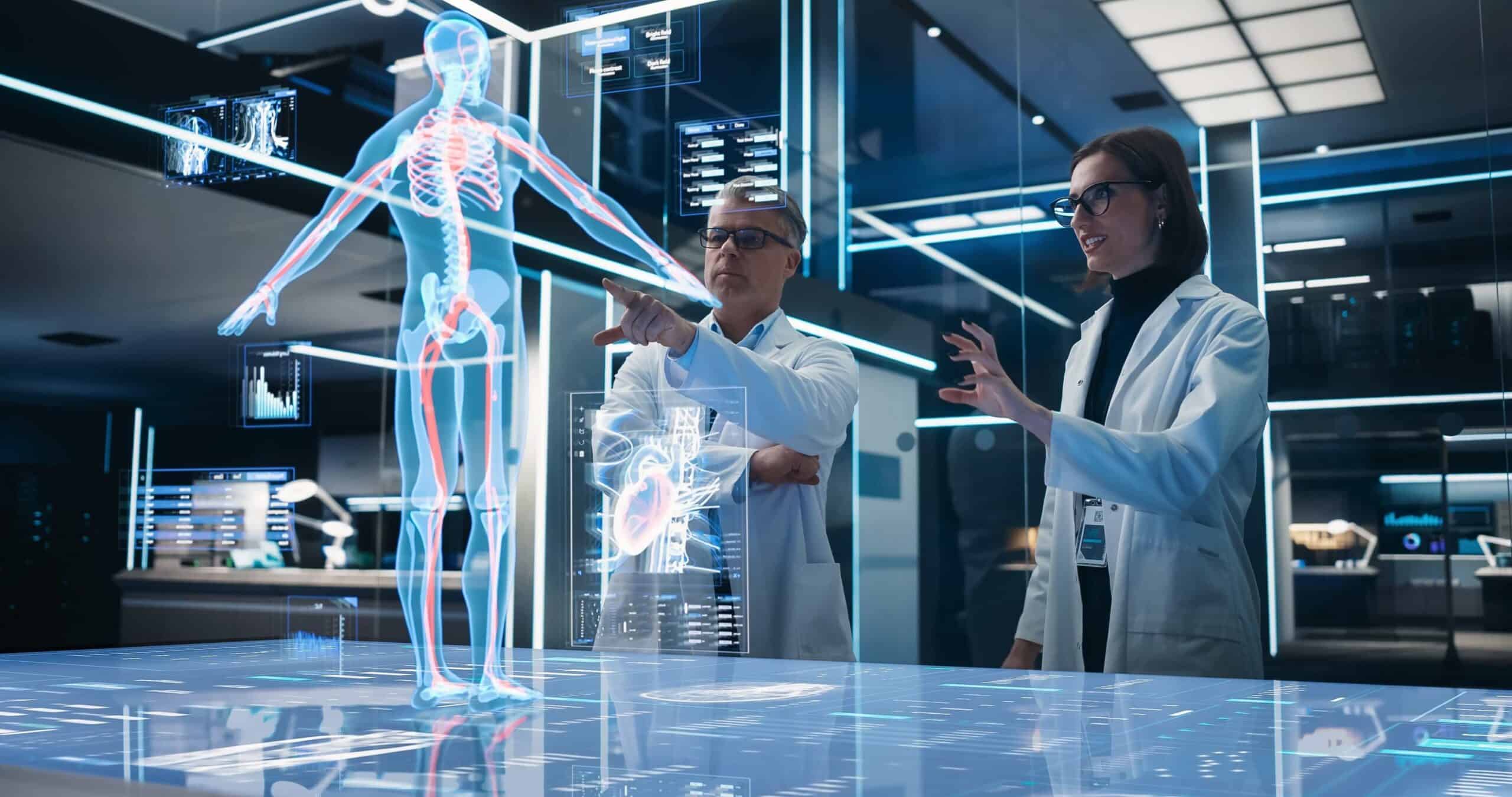

But as awesome as they are, they produce flat, 2D images that have to be imaginatively projected by your doctors. That is, they see you and use the images they’ve gathered to imagine what’s going on inside. They can’t see you and the images at the same time, so they have to use what they know to make an educated guess about what’s happening. But Watts and Fiest want to revolutionise how doctors visualise this data, allowing them to skip the imagination and really ‘see’ what’s inside you. As Watts explains, “We wanted to create a system that would show clinicians a patient’s internal anatomy within the context of the body.”

Seeing inside a patient – without a scalpel

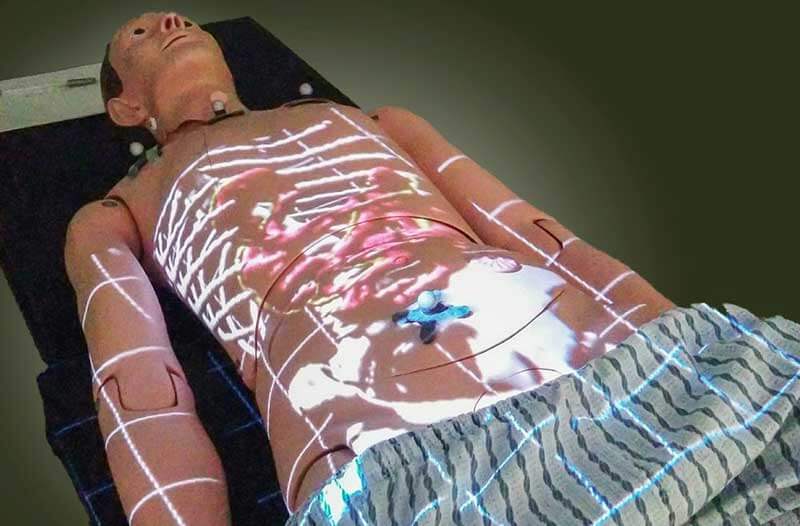

“It’s like if you had a flashlight, and you could select a part of the body and show what’s inside,” he says. “If someone was standing, you could shine this projector at them and you could see their rib cage, spine, or other internal organ[s].” Here’s how it works. A patient is first scanned, generating the images the medical team needs. Using an advanced projector mounted above the patients, these images are then superimposed over their body. Using delicate, infrared motion trackers, the images are moved in tandem with them, so as they roll, twist, or turn, so too does the display. This allows doctors to ‘see’ the complex images discovered by CT or MRI, giving them a precise picture of everything they need to know, from bones and blood vessels to organs and other soft tissues.

Watts and Fiest are refining this motion-sensing calibration, and they’d like to offer depth sensors. According to Leif Johnson at TechRadar, it already includes the option of allowing physicians to customise what they see. For instance, they can choose to display only some of the composite images.

ProjectDR moving forward

The next step in ProjectDR’s development is to include it in surgical simulations. If the tech works as it should, it will move on to actual surgeries, where it will help physicians plan and execute procedures. But it has other uses, too. “There are lots of applications for this technology, including in teaching, physiotherapy, laparoscopic surgery and even surgical planning,” Watts says.

For students of anatomy, physiology, and physical therapy, the possibility of seeing inside a patient is simply amazing. Forget textbooks or dissection – these students might soon examine a real-life patient whose broken bone has been set, and get to actually see the repair. That’s game-changing for teaching.