- Robots deal with radioactive material at Fukushima

- DARPA pours money into subterranean SAR solutions

- Microrobots come in swarms to look for survivors

- The Centauro is a rescue machine of impressive strength

- ‘Soft’ robots can reach places inaccessible to many other robots

- Getting ready for the next catastrophic event

We are living in one of the most perilous eras of Earth’s history, in which natural and man-made disasters alike are constantly ravaging the planet. Earthquakes, tsunamis, building fires, and mining accidents are just some of a number of threats humans have to face every single day. In fact, climate-related and geophysical disasters alone killed 1.3 million people between 1998 and 2017, taking an especially heavy toll on the world’s poorest nationsand leaving an additional 4.4 billion people injured, homeless, or displaced. And as this trend continues with no end in sight, it’s become paramount to safeguard human lives and improve the efficiency of search and rescue (SAR) operations.

Currently, SAR missions are often time-consuming and dangerous, as teams pass through narrow passages and even cause secondary damage. Some areas can also be inaccessible due to collapsed buildings or gas leaks. This wastes precious time, which is why tech firms are stepping up their efforts to create robots that can help rescuers to safely and quickly execute their missions. Some of these machines are already deployed and work in hazardous environments, while others are still in development and might take years to launch. Once deployed, though, they’ll help rescuers find survivors, remove debris, and map disaster scenes.

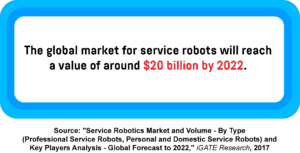

Robots designed for disaster and emergency response are a part of a thriving global service robotics market that’s set to reach a value of around $20 billion by 2022. And as robots become cheaper and powered by increasingly powerful technologies, their use will increase too, helping to save the lives of a growing number of people.

Robots deal with radioactive material at Fukushima

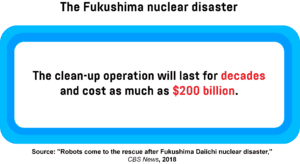

A powerful earthquake and the tsunami that followed triggered one of the worst nuclear disasters in human history that took place at Japan’s Fukushima Daiichi Nuclear Power Plant in 2011. As three reactors went into meltdown, the uranium turned to molten lava and burned through steel walls and concrete floors, leading to radioactive contamination of the reactor buildings. A massive clean-up operation was launched immediately after the disaster, but it will take decades to complete and may cost as much as $200 billion. The key part of these efforts, though, are robots developed in a nearby $100-million-worth research centre built by the Japanese government in 2016.

In February 2019, the Tokyo Electric Power Company (TEPCO) that manages the damaged power plant achieved a major breakthrough. It used a robot equipped with a camera, a radiation dosimeter, robotic ‘fingers’, and various other sensors to inspect six locations at which fuel debris is located. The machine confirmed that the material can be lifted and moved at five of the locations, while at the remaining one it was firmly cemented in place.

This was the first time that TEPCO was able to touch radioactive sediments and inspect the state of the melted fuel at the Unit 2 reactor. During the mission, the robot also collected a wealth of data, such as radiation levels, temperature, and images that will later be analysed to determine the best course of action. As it stands, the retrieval of fuel debris is expected to begin in 2021, but it remains to be seen whether such plan is even feasible.

DARPA pours money into subterranean SAR solutions

The Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency (DARPA), an agency of the US Department of Defense responsible for emerging technologies, is known for its investments in robotic technology. One of its funding programs is the multi-year Subterranean Challenge, an endeavour to “explore new approaches to rapidly map, navigate, search, and exploit complex underground environments, including human-made tunnel systems, urban underground, and natural cave networks”. In other words, DARPA seeks technologies that will help soldiers and first responders to more easily navigate in mines, caves, and subway stations.

One of the teams competing for up to $2 million worth of funding is a team composed of students coming from Carnegie Mellon and Oregon State University, who are working on an SAR solution that consists of a four-wheeled rover and a small drone. The rover is equipped with a 3D camera and lidar tech that allow it to navigate and map environments such as underground mines. As it moves, the machine also drops Wi-Fi repeaters behind it to extend its signal. The drone, on the other hand, is capable of flying through narrow passages. Equipped with multiple sensors, it’s designed to take over the search once the rover encounters an obstacle it can’t overcome.

The team is still testing the solution and trying to find a way for the rover and the drone to operate in tandem. There is enough time, though, as the final event on which DARPA is set to announce winners is planned for 2021.

Microrobots come in swarms to look for survivors

Meanwhile, Kevin Chen and several other postdoctoral fellows have developed Harvard’s Ambulatory Microrobot (HAMR), an insect-like robot that could provide major assistance to first responders. The idea behind this project is to deploy a large number of cockroach-sized robots to inspect a collapsed site, find survivors, and transmit their location to rescue teams. This would be both faster and safer compared to traditional SAR methods.

The microrobot currently moves at a speed of 25 cm per second on both water and land, and comes with integrated solar cells. A single HAMR takes one week to develop and costs around five dollars, although Chen plans to cut the production time to five human hours per device. A major drawback of the existing design is that it makes the machine useless in underground areas with limited exposure to sunlight. But that’s an issue the scientists plan to tackle in the near future, along with making the robot easy to fix and able to survive collisions. The search and rescue deployment of this device, however, will require an additional 10 to 20 years of research.

The Centauro is a rescue machine of impressive strength

Funded by the European Commission, researchers at IIT-Istituto Italiano di Tecnologia took a different approach compared to their Harvard colleagues. The Italians assembled a 1.5-metre-tall and 65-centimetre-wide robot, dubbed Centauro, that weighs an impressive 93 kilograms. The payload capacity of its single arm is around 11 kilograms and the battery can last for up to two and a half hours. Cameras, colour and depth sensors, and a lidar scanner are located in its head, while the robot is also equipped with three on-board computers dedicated to real time control, motion planning, and perception processing.

Clearly, Centauro is a robust machine that can be used in various disaster relief scenarios. It can easily navigate complex terrain, pass through narrow corridors, climb stairs, carry a heavy load, manipulate powerful tools, and sustain harsh interactions. And although Centauro is currently remotely controlled, researchers plan to provide it with more autonomy so that it can operate on its own. In the next stage, the robot will be tested in real-world scenarios, such as ruined buildings or hazardous environments that are too unsafe for human rescuers to venture into.

‘Soft’ robots can reach places inaccessible to many other robots

When it comes to reaching tight spaces that humans can’t access, a team from the University of California San Diego thinks that the answer lies in so-called ‘soft’ robots. In 2017, engineers at this institution developed a small, four-legged machine with inflatable chambers inside its squishy legs. This makes the robot flexible enough to navigate rough terrain and crawl or walk on sand, rocks, and inclined surfaces. The key to producing this robot is a 3D printer “that can print soft and rigid materials together.”

A team at Brigham Young University led by Marc Killpack, a professor in the Department of Mechanical Engineering, is also developing a ‘soft’ robot named King Louie. The robot needs to be inflated before it’s used, and it was developed for NASA, which hopes the device may one day replace existing robotic arms used on rovers, shuttles, and space stations. Furthermore, Killpack says that King Louie can also be used in SAR missions. For instance, rescuers could easily transport the deflated robot and then assemble it for use in hard-to-reach disaster sites.

Getting ready for the next catastrophic event

First responders are facing a multitude of challenges every day. Earthquakes, mining incidents, building fires, and floods are just some of the many extreme events that claim the lives of thousands of people. And with climate change showing no signs of slowing down, we can expect the natural and man-made disasters to be even more devastating in future.

Technology could provide a way to save more lives and make emergency response operations faster and safer. Whether it’s swarms of microrobots, drones, powerful Centauro machines, or robots resistant to radiation, humans will have an increasing number of devices at their disposal with which to reach disaster sites and save victims. This is a reassuring fact in an age when lives are easily lost, but could also be saved just as easily. And although predicting the next catastrophic event remains difficult new technologies and innovative trends ensure that one day rescue robots will be the first thing that survivors will see.