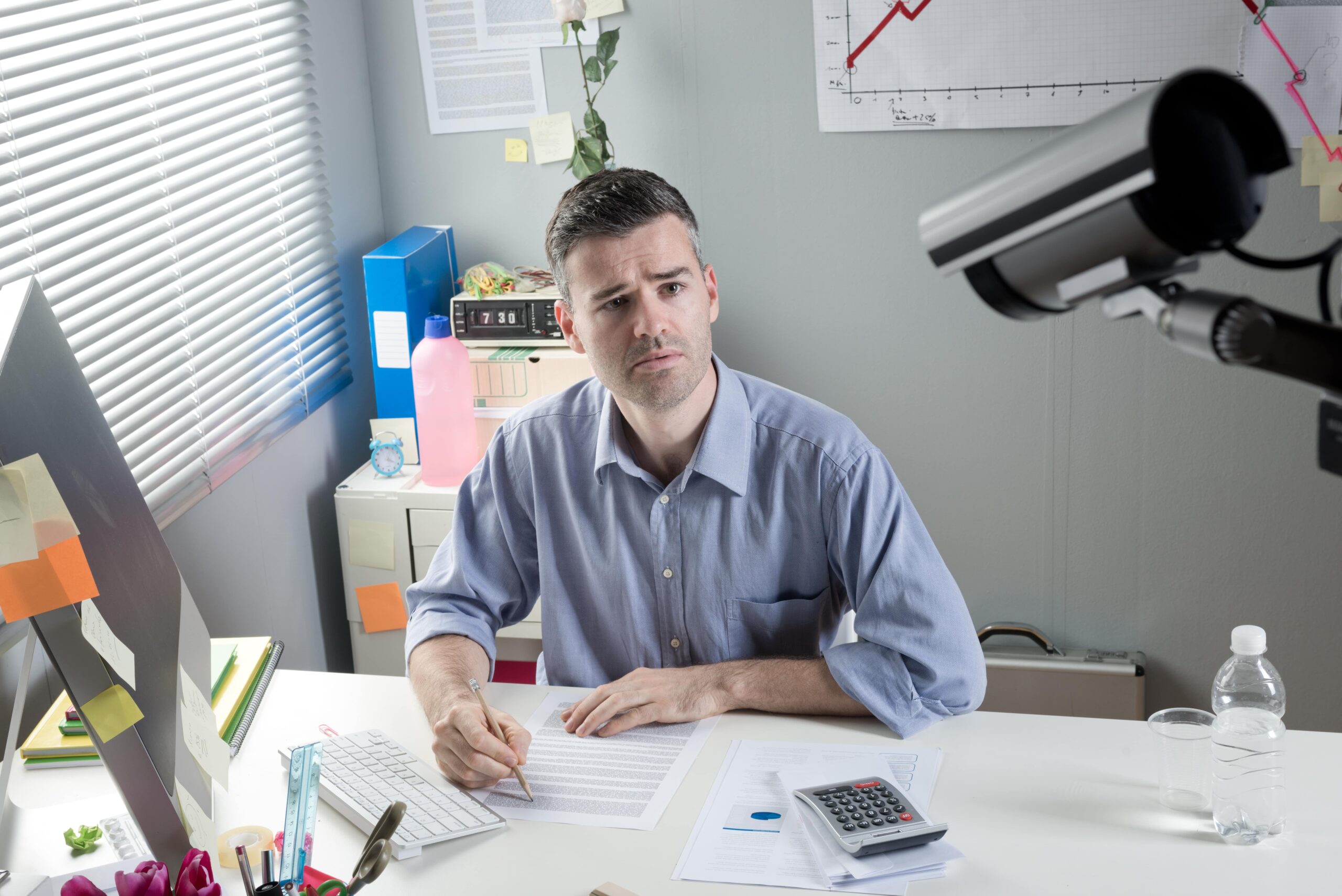

- You’re being watched

- The rise of bossware

- The illusion of consent

For years, workplace monitoring has been a familiar part of the employment experience. From security cameras in office corridors to the occasional email audit, employees have grown accustomed to a level of oversight aimed at maintaining productivity and protecting sensitive company information. However, the tide is turning, and HR leaders are increasingly deploying sophisticated monitoring software, ushering in an era that may redefine the boundaries of workplace surveillance. In this brave new world of digital supervision, an unsettling question arises: Are employees aware of the extent to which they are being monitored? In many cases, the answer is no. The shadow of surveillance has grown longer and more intricate, often shrouding itself in the cloak of invisibility. As we delve deeper into these technologies, we must critically examine where the line should be drawn to preserve the delicate balance between organisational efficiency and individual privacy.

You’re being watched

The roots of modern workplace monitoring extend far back in time, finding their origins in the innovative yet controversial Panopticon system introduced by the 18th-century philosopher Jeremy Bentham. This concept, although conceived centuries ago, remarkably mirrors the core principles that continue to drive contemporary workplace surveillance. At its essence, the Panopticon was a model of social control, where a central overseer possessed comprehensive access to the activities of individuals — what they did, who they interacted with, and when — all with the ability to apply discipline as deemed necessary. “The principle is central inspection”, explains Philip Schofield, professor of the History of Legal and Political Thought and Director of the Bentham Project at UCL. “You can do central inspection by CCTV. You don’t need a round building to do it. Monitoring electronic communications from a central location, that is panoptic. The real heart of Bentham’s panoptic idea is that there are certain activities which are better conducted when they are supervised”. The essence of constant observation, even when awareness exists, has perpetually stirred controversy and, at times, resulted in abuses of power. Today, the landscape of workplace monitoring has evolved in response to the birth of the digital age. What was once the Panopticon is now often realised through a suite of surveillance software collectively known as ‘bossware.’ In this modern era, most employees are well aware that their employers have extended their watchful gaze into the digital realm. However, the concerns and ethical dilemmas that have accompanied workplace surveillance through the ages persist, as the tools employed have become increasingly sophisticated and intrusive.

The rise of bossware

In recent years, workplace surveillance technology has risen in notoriety, particularly gaining prominence as organisations transitioned to remote work setups. 86 per cent of all employees in a survey by Digital.com report being made aware of its use by their employers — which means, of course, that 14 per cent were not. These technologies wield an astonishing breadth of reach, enabling the monitoring of everything from the websites employees peruse to the minutiae of their interactions with colleagues, even down to the precision of their keystrokes. One example of bossware is EmailAnalytics, which silently tracks all employees’ email activity, both in terms of content and response times. The information is then arranged into tables and graphs so that management can gain insight into average email response times, top senders and recipients, and activity levels over the course of the day. Similarly, ActivTrak extends its digital tentacles to monitor not only the hours employees clock but also their engagement levels. This multifaceted software can even distinguish between productive and unproductive behaviors, as well as active and passive conduct, by meticulously tracking mouse movements, keyboard activity, and the usage of websites and applications. While these examples may appear relatively innocuous, they underscore a growing unease among many employees. The use of certain bossware solutions, ostensibly implemented to boost productivity, is, in reality, fostering a climate of distrust and, in some cases, even resentment towards organisational leadership.

The illusion of consent

Bossware can, in some cases, lead to a decrease in employee morale and productivity, as feelings of anxiety and self-consciousness overwhelm the ability to put out quality work. The implicit message that your manager does not trust you without monitoring every keystroke is not necessarily conducive to positive outcomes. Then there are privacy concerns: many employees use the same device for their personal lives and their work, particularly when a device is not supplied to them. Furthermore, the flexibility offered by hybrid models may see employees working late to allow them to attend to personal matters during the day. However, bossware generally cannot distinguish between business and personal matters, with all kinds of personal information being swept up into its vortex. As such, employees (particularly those uninformed or under-informed ones) may inadvertently be exposing all kinds of sensitive information — their passwords, their medical information, and conversations with loved ones — to their managers.

Many employees will not speak up about it, however, as they fear being singled out and subjugated. Managers will, in many cases, hammer upon the consensual nature of their monitoring practices. But the truth is that it is coercive — consent in the workplace, after all, is not real consent. Faced with the binary dilemma of either embracing intensive surveillance or facing unemployment, the overwhelming majority are left with no alternative but to accept the former. It’s not a ‘real’ choice, in this sense — but once the paperwork is submitted, it becomes a legally-binding one. In this disconcerting context, employees find themselves navigating treacherous waters with scant protections against the relentless tide of workplace surveillance. These safeguards come into play only when egregious overreach or harassment is evident, leaving the broader spectrum of monitoring practices largely unchecked.

Closing thoughts

Most employees understand and accept that when they receive a work device, a degree of monitoring is going to come alongside it. In some cases, it can, indeed, help improve productivity. But many employees fail to recognise the scope and scale of many bossware solutions and its potential to expose deeply sensitive information to their employer. Therefore, HR managers and organisational leaders must pause and reflect on their objectives when contemplating the implementation of surveillance tools in the workplace. Instead of a one-size-fits-all approach, there must be a thoughtful and transparent dialogue about the goals, methods, and the extent of monitoring required to achieve them. Striking a balance between maintaining productivity and respecting individual privacy and autonomy is not only an ethical imperative but also a strategic one. A workforce that feels respected and trusted is more likely to yield the innovation and dedication that every organisation desires.