- Why some countries ban phones in schools

- The many benefits of mobile devices in classrooms

- The impact of mobile apps on language learning

- Google’s new app helps students improve their reading skills

- What would be the best legacy of today’s schools?

The world has changed ever since smartphones have come to dominate our lives. They’ve put the internet in everyone’s pocket and transformed the way we communicate, work, and study. And millions of people across the world, especially teens, are arguably addicted to their smartphones. Such behaviour has led to a number of unwanted consequences. Many teachers and parents, for instance, believe that screen time prevents students from focusing on their classes and causes conflict with school authorities. Smartphones are sometimes even linked to mental health problems, such as anxiety and depression.

Due to these reasons, some countries have decided to completely ban mobile device use in schools. But since we live in the digital age, where technological literacy is an important aspect of a child’s education, banning smartphones might not be such a good idea. Smartphone apps are effective learning tools, especially when it comes to mastering new languages and improving reading skills, which are benefits that can’t be overlooked.

Why some countries ban phones in schools

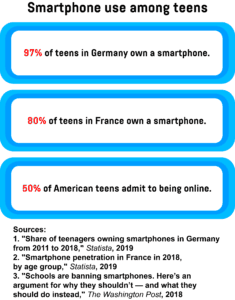

France, for example, banned the use of smart devices in schools for students up to age 15, while UK’s politicians are also considering such a change, with various other countries likely to follow suit. What prompted these policies is that mobile devices are increasingly dominating children’s lives. 97 per cent of teens in Germany and 80 per cent in France own smartphones, while half of American teenagers admit to being online non-stop.

And a study published in the Journal of Communication Education shows that banning phones can help students to write down 62 per cent more notes in their notebooks and remember more of what teachers are explaining in class. Also, researchers at the London School of Economics have found that phone bans lead to higher test scores, especially benefiting low-performing students. Spending time on screens is increasing the risk of children developing anxiety and depression, as well as leading to less curiosity and self-control.

With these facts in mind, banning phones from schools comes as no surprise. But while such a decision might provide some short-term benefits, in the long-term, it prevents students from benefiting from the latest technologies that can improve their learning experience and prepare them for the future labour market.

The many benefits of mobile devices in classrooms

Jamie Brooker, a co-founder of the game-based learning platform Kahoot!, says that instead of phone bans, politicians should help educators to turn “these powerful devices into genuine learning companions”. And many teachers are already showing how it can be done. Astrid Natley, an English teacher at a secondary girls’ grammar school in Lincolnshire, argues that phones are invaluable tools, as they enable students to record their work, take photos, engage in group quizzes, and adjust the font size if they have reading difficulties. Furthermore, smartphones enable children to find information, benefit from personalised learning, and test new apps and software tools. Natley adds that “If we stop children using phones, then we’re rejecting something they care about. Phones are important for them and that’s not going to change.”

For some parents, phones are also critical, because they allow them to stay in touch with children who suffer from certain medical conditions. Kay Bellwood’s son, for instance, uses his phone to track blood glucose levels and can send an SOS signal to his parents if he’s unable to walk or talk due to type 1 diabetes. And in a world where smartphones are ubiquitous, blanket bans seem like an easy, but short-sighted solution. Schools would do better to teach children how to use mobile devices in a responsible way and lead healthy lives.

To that end, the education expert Pasi Sahlberg argues that the first step is for parents to motivate their children to sleep more and not to use phones two hours before bedtime. Also, children should spend more time outdoors and read more books. In Finland, one in eight boys are functionally illiterate, as fewer and fewer of them read for pleasure. And as children use cyber slang shortcuts and symbols to communicate online, writing proficiency is rapidly deteriorating. Sahlberg advises schools to pay more attention to writing skills. And lastly, he proposes responsible and time-limited use of smartphones on a daily basis, with parents and teachers setting an example that children can follow.

The impact of mobile apps on language learning

Used responsibly, smartphones can help users overcome major obstacles, such as learning a new language. Thanks to phone apps, people can learn at their own pace, which is rarely the case with traditional language courses. In fact, many people use apps for practical reasons. For instance, according to a survey conducted by the research company CivicScience, 25 per cent of respondents rely on apps to become fully fluent in a new language. The same survey reveals that only four per cent use language learning apps as a form of entertainment. With this in mind, companies are putting a lot of effort into their app development to provide users with even more innovative language learning apps.

One of the most recent solutions comes from a team at Microsoft, which developed an app called Read My World to help users improve their English literacy. The app allows users to take pictures of objects surrounding them, after which it uses computer vision to identify what’s on the picture and provide the correct spelling and pronunciation of the word. Microsoft’s technology also features vocabulary games, so that users can practice their newly discovered words and memorise them. The app can be used as a supplement to traditional language learning in a classroom, but it’s also a great solution for people who don’t have the time or money to attend language learning classes.

Another innovative app was launched in 2019 on the crowdfunding platform Kickstarter. Described as “The first language learning app built for your tongue, not your thumb”, Magiclingua promises it will help users to start speaking any “new language from day one”. Within the app, users will first watch a video lesson to understand the grammar and its principles. In the next stage, they can start practicing their speaking skills with a smart conversation bot. The solution is designed to be patient throughout the process. Since users aren’t speaking with a real person, they won’t feel embarrassed or worried about what people might think about their language skills. Once the user has become more confident speaking a new language, the final step in the app is having a real conversation with a native speaker. The app is expected to be available in the iOS and Android app stores in late 2019.

Just like with every other innovation, there are concerns that language learning apps could eventually replace traditional language classes. Also, there’s scepticism surrounding the apps’ usage and effectiveness. To understand how these solutions work, and if they’re really that effective, researchers from Yale University’s Center for Language Study conducted a study on 117 participants who used a commercial language learning app called Babbel to learn Spanish. Babbel features short lessons that focus on everyday conversations. As the users speak, the app listens carefully to identify their pronunciation.

At the beginning of the study, all participants were beginners in Spanish. After three months of using Babbel, the participants were asked to take an online test, so they can be categorised based on their proficiency level. Existing categories include novice, intermediate, advanced, and superior proficiency. According to the results, 79.5 per cent of participants were placed into the novice category, while 20.5 per cent reached the intermediate level of proficiency. As for learner experience, the study shows that 91 per cent “enjoyed using the Babbel app”, while 75 per cent said the app helped them achieve their goals. The researcher Nelleke Van Deusen-Scholl claims the app did a good job in helping people reach the basic level of proficiency. But “after that, you need to go out and meet other speakers,” says Van Deusen-Scholl.

Google’s new app helps students improve their reading skills

To help students improve their language skills, Google launched an app called Bolo. Bolo is designed for elementary school students in India, and it uses speech recognition and text-to-speech technology to help students learn to read in Hindi and English. Bolo is equipped with a catalogue of 40 stories in English and 50 stories in Hindi. It also features a reading assistant called Diya. As the student reads aloud, Diya will listen and provide feedback. It can also read stories to the students and explain the meaning of particular words. And to motivate them even more, Diya gives them word games through which they can earn in-app rewards.

Since the app works offline, it’s the perfect solution for students who don’t have access to the internet. Bolo has already been tested in 200 villages in the Uttar Pradesh region, where it proved to be an efficient learning tool. TechCrunch reports that 64 per cent of children who used the Bolo app improved their reading skills in three months.

What would be the best legacy of today’s schools?

Thanks to technology, education is no longer confined to monotone lectures and dry textbooks. Today, students can enjoy interactive and immersive tools that make studying fun and engaging. Mobile apps, embedded with audio, video, and other innovative capabilities are revolutionising learning experiences. And they’re here to stay, as people are bound to use them more and more. Phones make learning a language easier and are a good solution to the teacher shortage in other courses, too. And companies already produce advanced gadgets and wearables that might make cell phones look like an outdated concept one day. Making sure that future generations know how to use technology as a force for good and self-improvement could be the best legacy of today’s schools.