- We’ll probably need to get off Earth to survive

- Our propulsion systems are too slow for deep space

- Therapeutic hypothermia is already being used in medicine

- Is induced torpor the future of space flight?

- We’ll still need sleep – hibernation doesn’t provide that

- Zero G and health risks

- Hibernation solves a lot of space travel related problems

Suspended animation for deep-space travel is a staple of science fiction. It’s a nod to the realities of exploring deep space and the mind-bendingly vast distances we’d need to cover. Our closest exoplanet, Proxima b, is 4.25 light-years away. And while that may not sound too bad, current tech can’t get us even close to speeds that make that a manageable distance. As Sarah Marquart, a science writer for Futurism, reminds us, “New Horizons, the fastest spacecraft to leave Earth, took nine and a half years to reach Pluto”.

But don’t let that dim your enthusiasm! In addition to new engine designs, ranging from ion drives to radio frequency resonant cavity thrusters, scientists are working on putting explorers to sleep for much of the journey. This will save food, air, fuel, and money – and it might just save lives, too!

We’ll probably need to get off Earth to survive

It’s important to realise that, if we fail to explore deep space, we’re dooming ourselves. When Stephen Hawking speaks about issues like this, it’s with real authority. And as he told Big Think, “I believe that the long-term future of the human race must be in space. It will be difficult enough to avoid disaster on planet Earth in the next hundred years, let alone the next thousand, or million. The human race shouldn’t have all its eggs in one basket, or on one planet. Let’s hope we can avoid dropping the basket until we have spread the load”. The only way to do that is to explore our neighbouring planets, Venus and Mars, before thinking even more far afield.

Our propulsion systems are too slow for deep space

But with current tech, even reaching one of our closest neighbours, Mars, is a six month trip. And that presents real obstacles for human explorers. They need water, food, and oxygen for the journey, space to move around, exercise to keep them fit in zero gravity, and tough shielding to prevent deadly exposure to radiation on-route. When you add up the solutions to those problems, the trip quickly gets expensive, and the size of the ship necessary to meet those needs grows even faster.

Therapeutic hypothermia is already being used in medicine

But there may be a solution first explored in medical science. Doctors have been using a technique called therapeutic hypothermia to save patients’ lives. You’ve probably heard of someone who fell into icy water, stopped breathing, and was later saved. The basic principle is the same. By gently cooling the body, medical teams can slow a patient’s metabolism, mimicking the hibernation that some mammals use to get through long winters. For each degree C that the core temperature is dropped, there’s a corresponding 7 per cent decrease in metabolism. And by gently lowering that temp, but keeping it high enough to preserve the heartbeat and respiration, doctors can keep people alive who might otherwise die. It’s not unusual for a patient to be placed into therapeutic hypothermia for as many as 4 days, and in China, a few patients have been cooled for as long as two weeks with no adverse effects.

Is induced torpor the future of space flight?

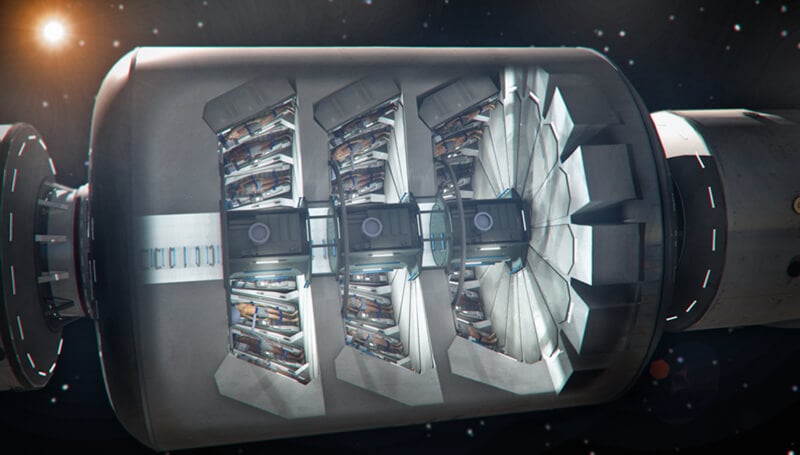

Scientists are now researching this technique for space travel, but don’t be misled by movies like Passengers. The reality of suspended animation, a term these researchers hate, is a lot less sexy. John Bradford, an engineer and the CEO of SpaceWorks, is experimenting with what he prefers to call induced torpor. He offers a reality check, too, as we’re not talking about Sleeping Beauty. Instead of the individual pods you see in movies, Bradford’s looking at small rooms for the crew where they cycle in and out of unconsciousness. “There would be some robotic arms and monitoring systems taking care of the crew. They’d have small transnasal tubes for the cooling and some warming systems as well, to bring them back from stasis”, he told Quartz. Keeping people in induced torpor for long periods is probably dangerous, so he’s thinking about cycles of ‘sleep’.

We’ll still need sleep – hibernation doesn’t provide that

And speaking of sleep, that’s a problem. It turns out that while you look like you’re resting, hibernation doesn’t give your brain and body the sleep it needs. As Jessa gamble writes for The Atlantic, “Hibernation may involve lying down with one’s eyes closed, but there’s no sleeping going on; in fact, a long stretch of it leaves the body sleep-deprived. If the movie Passengers were true to life, the first thing that would happen when Jennifer Lawrence opened her long-lashed eyes in the hibernation pod would not be her listening to the ship computer’s crew update. It would be her closing those long lashes again and descending straight into sleep”.

Zero G and health risks

Another problem is that long periods of time in zero gravity are simply terrible for us. Bradford’s working on solutions drawn from how we deal with comatose patients. “We have ideas how to exercise them […] neuromuscular electrical stimulation”, Bradford says. Basically, by stimulating muscles directly with electrical current, you can get them to contract much like they do during exercise. “There are very promising results in using this technique on comatose patients to prevent muscle atrophy,” he added. And with the help of medicines to preserve bone density and prevent fluid moving to tissues where it shouldn’t, we can probably keep the crew healthy. That’s another reason he likes the idea of explorers who sleep in shifts: one group can monitor and treat the others, cycling through waves of attendants and sleepers as they journey.

Hibernation solves a lot of space travel related problems

But as Bradford thinks his way through the technical challenges, it’s pretty clear that some form of suspended animation is a solution to the obstacles of deep space exploration. For instance, with the crew asleep for much of the journey, the need for food, water, and air is drastically reduced. Moreover, because they’ll be more confined during the journey, it’s easier to protect them from radiation – only the cabin really needs to be shielded against the threat. And because the crew won’t be awake, their need for entertainment and psychological breaks from small spaces, confined quarters, and simple boredom won’t be as pressing.